From mid August until the end of September 2014, I spent 6 weeks on an artist residency at a foundation called Arquetopia, based in the city of Oaxaca, Mexico learning traditional weaving techniques from local craftsman.

Oaxaca is an incredibly rich state culturally, with one of the most diverse indigenous populations within Mexico. The state is located in the southwestern region, encompassing terrain ranging from the Pacific coast to fertile fluvial valleys and high altitude mountain ranges. The historic town of Oaxaca sits inland in a valley surrounded by mountains.

There are officially 16 indigenous groups in the state of Oaxaca, Even within the predominant Mixtec and Zapotec indigenous groups, there are dozens of sub groups whose social and linguistic characteristics are so different they have little or no intelligibility between major ‘dialects’, partly due to the geographical diversity of the state.

Listed as a UNESCO world heritage site since 1987 along with the nearby archaeological site of Monte Alban, Oaxaca de Juarez was founded in 1529 in a small valley occupied by Zapotec Indians.

The town centre is a well preserved example of 16th century colonial architecture on a grid layout arranged around a central axis, not unlike the 'axis mundi' indigenous tribes planned their settlements around.

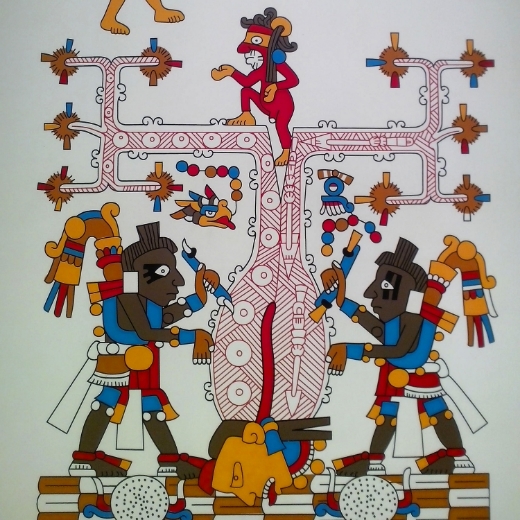

Like the earlier Olmec, Zapotec and Mixtec settlements, Oaxaca's colonial town revolves around the central site of ceremonial and religious importance, the Santo Domingo Cathedral.

The adjacent convent building is now home to the Museum and Cultural Centre, housing a large collection of Monte Alban's archaeological treasures.

The grand colonial architecture that defines the historic old town of Oaxaca as a UNESCO World Heritage site was likely built on top of a pre-existing settlement of both Mixtec and Zapotec origin. This was a common way for the conquistadors to develop new settlements, utilising stone from the existing temples, palaces and important structures.

Although excavations within the city are almost impossible due to the density of the existing settlement, targeted excavations have uncovered evidence of pre colonial palaces and structures beneath the colonial architecture.

'Monte Alban is the most important archaeological site of the Valley of Oaxaca. Inhabited over a period of 1,500 years by a succession of peoples – Olmecs, Zapotecs and Mixtecs, the terraces, dams, canals, pyramids and artificial mounds of Monte Albán were literally carved out of the mountain and are the symbols of a sacred topography. . .

The grand Zapotec capital flourished for thirteen centuries, from the year 500 B.C to 850 A.D. when, for reasons that have not been established, its eventual abandonment began.' http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/415

Oaxaca town was developed by Zapotecs as the main urban centre within the state of Oaxaca, with Monte Alban being the ceremonial centre, recognised throughout Mesoamerica.

Excavations from important tombs at Monte Alban have uncovered some of the most intricate and sophisticated examples of ceremonial craft work within Mexico, many of which are on display in the Santo Domingo Cultural Centre in the centre of Oaxaca town.

Around 800 AD the Zapotecs’ power declined and was surpassed by the Mixtecs, a people who worshipped their gods in caves or near sacred rocks rather than grand architectural offerings.

Some historical accounts record the Zapotecs and Mixtecs co-existing fairly peacefully in the Valley of Oaxaca, resisting outside attack until the Aztecs raided from the North and managed to take Mitla as a military garrison, just prior to arrival of the Spanish conquistadors and their subsequent occupation and settlement of the Valleys of Oaxaca in the early 16th Century.

The Mixtec influence is evident at the ancient burial site of Mitla ‘Place of the Dead’, an intricately decorated stone ruin in the valley of Oaxaca.

Although much of the ceremonial structure at Mitla was destroyed with construction of a grand cathedral after Spanish settlement, beautiful examples of the unique mosaic stonework survive in two remaining structures.

The stone relief is made with no cement, by fitting together perfectly shaped polished stones, a unique site in Mexico. The excellently preserved motifs of recurring geometric patterns are also reflected throughout the textiles, art and architecture of the area.

Learning about and seeing firsthand the amazing examples of weaving, ceramic, stone carving and metalwork originating from Oaxaca, has given me an insight into the maker’s environment, technical skills, historical and social landscape.

The sophisticated use of colour, symbolism and technique reveals a mastery of craft within Oaxaca that dates back to the early pre-classic period in Mesoamerica of about 1500 BC, while evidence of human habitation dates back as far as 11,000 BC. Exquisite examples of these art forms are found in national and international galleries, museums and collections and many of these practices are still alive and in production today.

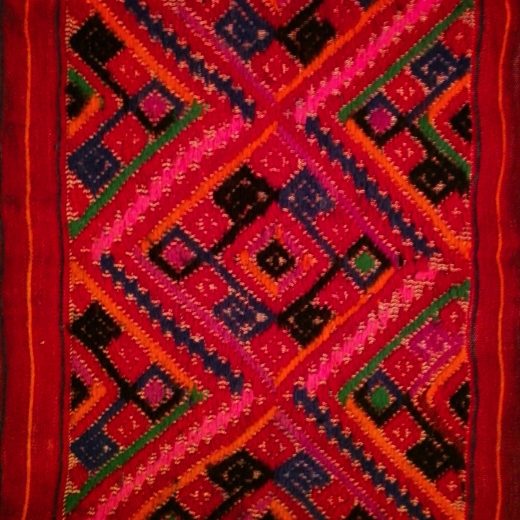

Weaving in particular is a very special part of Oaxaca’s heritage. The region's cultural diversity is represented through the symbols, styles, and colours within the textiles and these vary from village to village, so that one weaver may tell where a weaving comes from within the region..or even from which family.

Arquetopia’s instructional residency options and accommodating attitude provided the chance to learn some techniques local to Oaxaca, as a way to develop my technical skills and learn about the culture.

For the 6 week residency period, my time was divided into two lots of three weeks. First I received instruction from local backstrap loom weaver Eufrocina, followed by three weeks basket weaving using cane with Benito Lopez Antonio and his family in the nearby village of San Juan Guelavia.

Alongside the weaving instruction I spent any spare time exploring my surroundings as well as developing a self directed research project. My interest in the ways objects can serve to ‘map’ an environment and it’s cultural and social landscape drew me to the layers of history that surrounded me.

I began researching local forms of mapping, with a particular interest in what we choose to map and how different mediums can act as a record of a place in a more holistic representation than simply illustrating topography and environmental features.

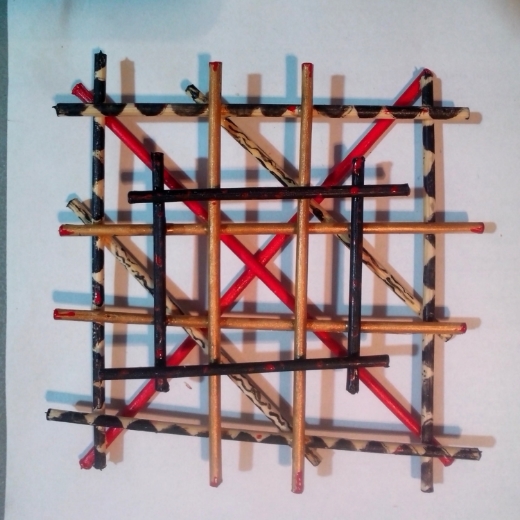

Leading on from the beginnings of some research from New Zealand into early Pacific ocean navigational tools (particularly stick charts), I started looking at what was important to mark for inhabitants of Oaxaca and the different methods and mediums chosen.

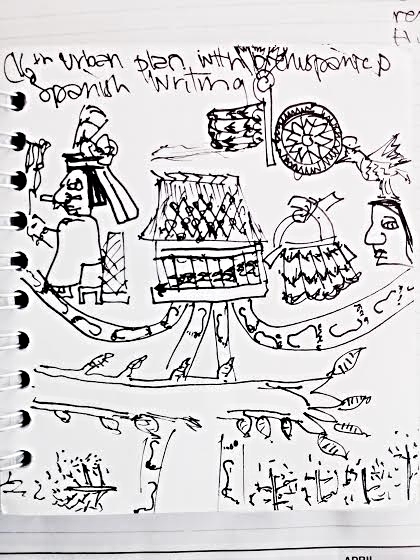

I began exploring forms to represent the grid layout of Oaxaca's historic town centre, building on the pre-Columbian ideals of a quadripartite division of space outwards from the ‘axis mundi’.

A discussion with historian Emanuelle Ortega led me to research the Relaciones Geográficas. This collection of documents were made in response to a questionnaire sent by the Spanish Crown to Mexico and the recently colonised territories in 1577, in order to record specific information about the 'New World'. The Relaciones Geográficas respond to specific questions on topics such as population, demographics, political jurisdictions, language(s) spoken, physical terrain, and native vegetation.

Of the 191 responses, about 77 were maps. Mostly these were drawn on Spanish paper by indigenous artists. Combining indigenous representation of social, physical, and cosmological aspects, with a local response to the information requested, resulted in unique and often beautifully rendered pictographs. These bi-cultural artifacts, dating from 1578-1586, are now considered a primary source of information about the Spanish Conquest of Middle America.

This research combined with the art and artefacts I was able to see in museums, galleries, private collections and in current production in Oaxaca, Mexico City, Chiapas, Campeche and the Yucatan gave me an insight into Mexico's history and cultural landscape through the objects produced by it's inhabitants.

Processing this information and visual material has been a huge inspiration to broaden my way of thinking about mapping of place and how I may navigate my own way of making, objects as signposts or markers of experience, place and memory.

With this in mind, receiving instruction in the traditional weaving techniques with practitioners who for whom the this has been a way of life for generations, linked a sense of history with a strong connection to the homes, everyday lives and collective histories that permeate the 'arte popular' of Mexico.

My first encounter with back strap loom weaving was in the village of Santo Tomás Jalieza with the famous Navarro family.

Living together around a central courtyard, mother Crispina, three sisters and brother Gerardo (a celebrated painter in his own right), share the space with their dog and chickens. The women spend their days weaving work that is in high demand for its vivid colour, fine technique and strong design.

Sought after by locals, nationals, tourists and collectors, the Navarro family sell only from their home by private appointment, allowing them full control over their work and profits.

Rhythmically winding the brightly coloured wool onto homemade spindles and then warping the basic wooden loom, we were treated to a demonstration that looks relatively fast and easy...until the pattern begins to emerge and Crispina jokes that it’s only when they’re getting into very involved discussions that her pattern count misses and she has to undo rows.

Dancers, flowers, even a deer pop out in primary yellow and red against the black background as Crispina silently counts, passing the weft over and under certain warp threads to form the design before the large wooden ‘machete’ spacer is flipped out, shuttle passed through the weft, machete re-inserted and battened down to tighten the weave.

These methods of weaving with the backstrap loom have been practiced in Mexico as well as other indigenous cultures for thousands of years, long before the Spanish arrived and introduced treadle looms, as evidenced in stone glyphs and codices that have survived the passage of time where thread could not.

The skill is passed down through families over generations and is still widely practiced, especially in Oaxaca. Renewed interest from the tourist market has helped support a resurgence within the industry since the 1970’s.

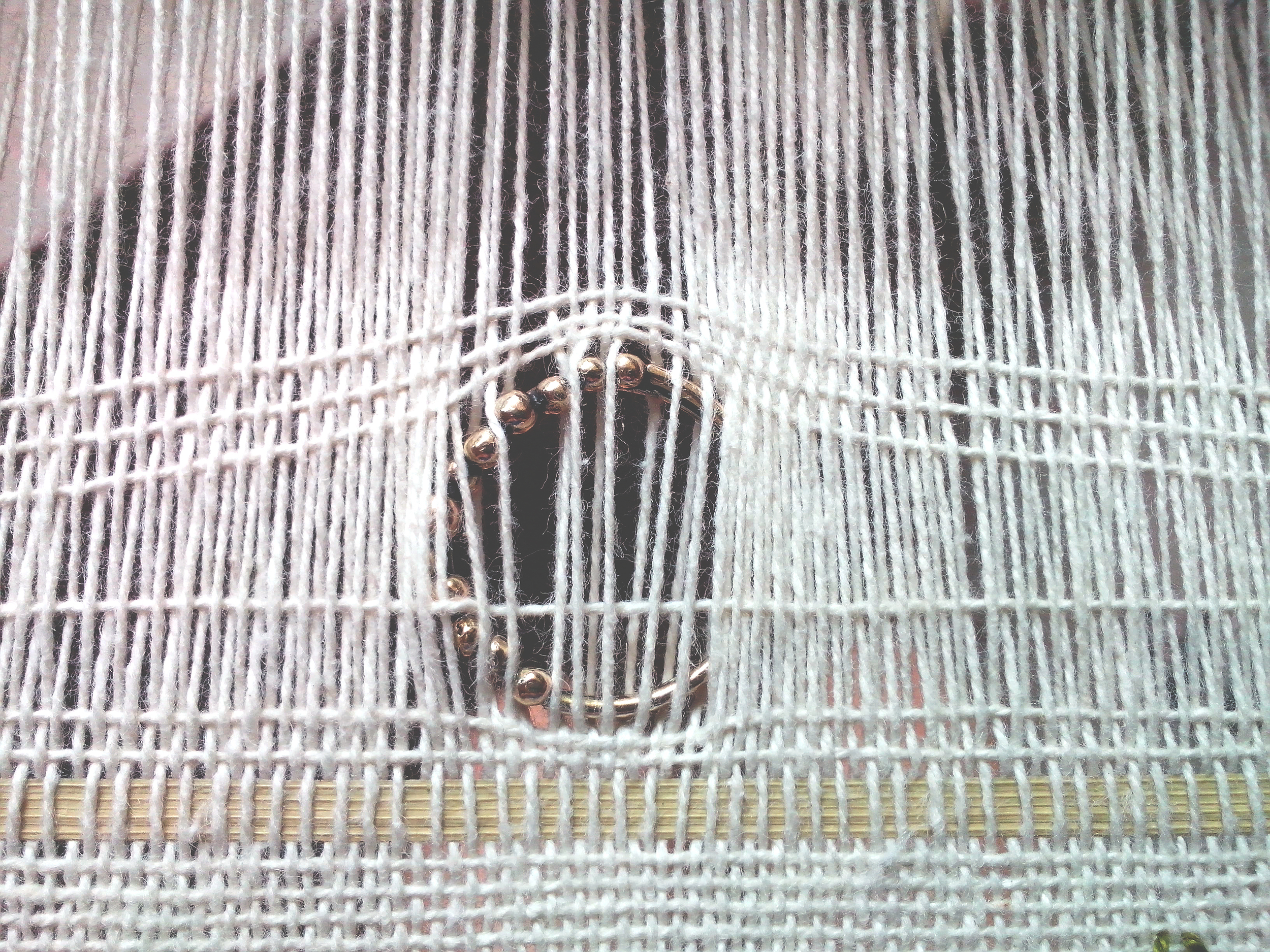

At the residency house, our teacher Eufrocina travelled from her village in the valleys of Oaxaca to patiently instruct my co-resident Tara and I in the technique of back strap loom weaving over two intensive weeks.

This type of weaving is different from the backstrap weaving the Navarro family were doing where their warp is a number of different colours, the weft is a single colour and they make all the patterns by passing the weft under and over certain warp threads.

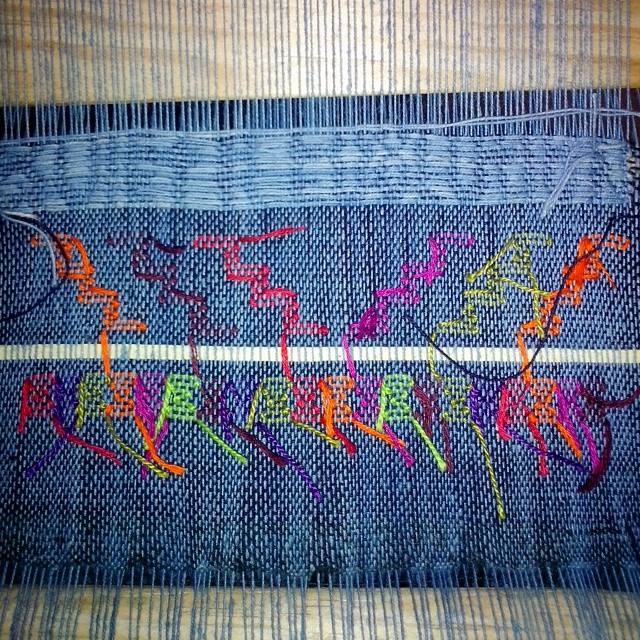

Eufrocina taught us a supplementary weft style of creating pattern within the weave which, as the name implies, involves adding in different coloured threads under certain warp threads and building up a pattern line by line, with the shuttle weft separating each line of supplementary weft.

Arriving at the residency space with warped looms ready to go on the first day and armfuls of her work to inspire us with designs (all for sale), Eufrocina showed us how to unwrap the rolled up loom and carefully tie one end to a pole/tree and strap the other end around our backs. This allows control over the tension of the loom which is an important part of the learning process.

Sitting on wooden stools and squinting hard at the intricate weave we were soon wise to the fact that short frequent breaks were necessary for our circulation. After managing an inch or so of basic weave, we both chose a two colour motif representing the lifecycle of maize to include using the supplementary weft technique.

Over the course of the week our 20cm wide samplers grew, more or less straight up and Eufrocina generously shared the traditional designs to help us make our own combinations all representing aspects of the lifecycle of a maize plant.

These designs are traditional for the area and on a deeper level symbolises the cycle of life. Choosing to reverse the central motif in my piece like a mirror image, Eufrocina delightedly pointed out it became a very special symbol, again representing the cycle of life.

There was a little lost in translation with my basic grasp of traveller’s Spanish and lessons conducted entirely in Spanish, but I am amazed at how much we were able to communicate with a few words, many demonstrations, strong Oaxacan coffee and some confused laughter.

Over the second week of instruction we were shown how to warp the loom and began on our second piece, which I chose to be more experimental with.

Eufrocina took us through the steps to prepare the cotton and warp the loom at her home in a village in the hills of Oaxaca.

Weaving is a family affair with her husband making tablecloths and bedspreads on the treadle loom and daughter working on the backstrap loom during holidays.

Working from the back as we were shown, it was some way in to my attempt to include a phrase in the supplementary weft design that I realised it would be the wrong way around from the front.

Another mirror image reversal and many scribbled notes with the pattern later I’m not sure I’ll attempt writing another phrase any time soon.

Palm leave made an interesting addition and I experimented a bit with including various objects within the weave with mixed success.

I intentionally left some of the weave to complete on my return to New Zealand so I could try out a few more ideas on sample number two.

Over this time my Australian counterpart, Tara Glastonbury and another Canadian resident Hannahlie visited many surrounding villages to see different types of weaving and stitchwork, black pottery, a cochineal farm at Tlapanochestli Grana Cochinilla, and a traditional paper making workshop at Casa, San Agustin Etla as well as sampling local delicacies including locally produced chocolate, fried grasshoppers, many local mezcal varieties and becoming regulars of the excellent Oaxaca Textile Museum.

The second part of my residency began about when the full force of rainy season hit town. Most days from early September at an unforeseeable time, the skies would darken, some rumbling would belch across the surrounding mountains, and whip cracks of lightning would signal the daily deluge.

Fortunately this didn’t coincide too often with my twice weekly instruction in cane weaving in the village of San Juan Guelavia.

The journey would consist of a 20 minute walk across town to the street corner where buses and collectivos (shared taxis) would stop to collect passengers going towards San Juan.

Flagging down a vehicle bound for ‘Tlacolula’ and being careful not to end up sitting in the front seat of a collective car, (the single seat accommodates two passengers in Mexico) the half hour ride would drop me, at my shouted request, by the turnoff to San Juan Guelavia.

Here I would stand under a tree until a small ute with covered back for passengers would arrive to pick us up for the village centre.

About 5km along the dirt road flanked by large maguey cacti we'd arrive in the centre of the small village outside the market.

On the appropriate street corner I would flag down a three wheel ‘moto’ driver to take me down the red dirt tracks to the house of Senor Benito, weaver of ‘canastas’.

Thankfully I was accompanied by the residency’s site manager Roberto on the first day. Communication was more difficult here, perhaps my accent and increasinging shyness at speaking Spanish (the more I was met with confused looks) combined with the bilingual Zapotec/Spanish accent of the Lopez family was the cause.

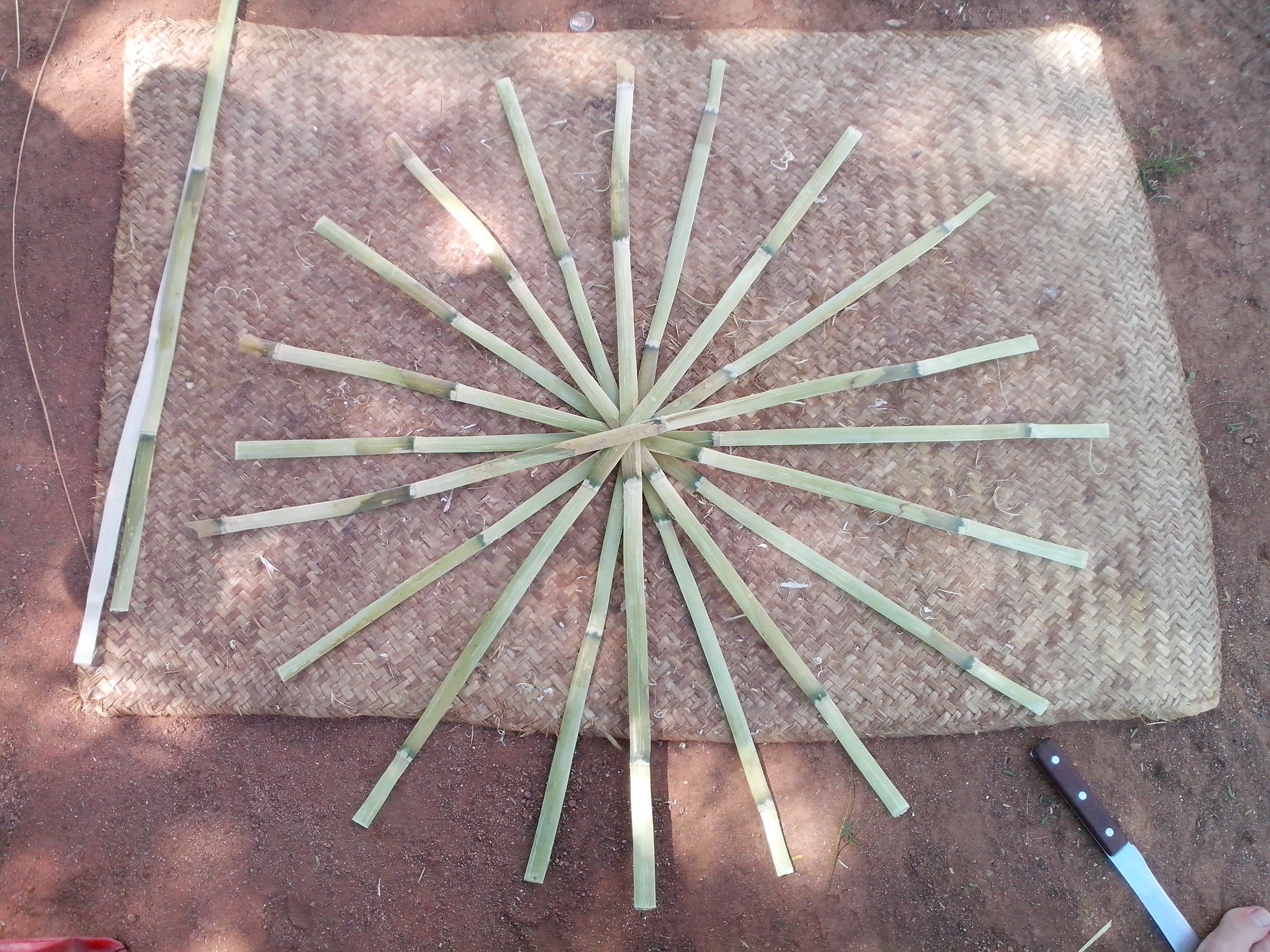

With perseverance and a few slashed fingers from the sharp cane shards, I managed to produce two beautiful cane baskets with much hands on help from my main teacher Benito within the 27 hours of instruction spread over three weeks.

My time was split between Benito’s father, (his co-teacher wife) and Benito. I began at the beginning, learning how to strip the outer husk from the cane into thin strips for weaving.

Despite my hours of practice I still found it hard to keep the long strips intact and couldn’t emulate Benito’s banana peel motion to remove the outer layer from the more flexible inner.

Later we walked through the sparsely vegetated undergrowth to a spot beside the dry river bed, to make a fire and roast lengths of cane, turning them until they steam from the inside out. From these we made the darker colored strips to use as decorative design elements in the baskets.

Despite the language barrier Benito, his wife and young family took me under their wing, as did their neighbours and extended family. On a few sessions that ran late to finish a task, I was fed beautiful homemade tamales, corn tortillas and beans with the famous stringy Oaxacan cheese.

The community’s friendliness and generosity are something I’ll always remember.

I gained more from the residency than I could have expected in knowledge and experience of Oaxaca, learning about the customs and traditions that draw from the past and inform the present.

While there were challenges and obstacles and I had hopes that were met in ways I couldn’t have foreseen, the experience gained and connections made during the residency will influence my work for years to come.

Coming from Aotearoa where weaving forms an integral and rich part of traditional and contemporary craft practice, the residency has helped me to see from a fresh perspective what it is that is so important about these practices.

Handmade objects have been used as everyday functional objects as well as in ritual and ceremonial symbolic functions for thousands of years.

Objects can embody aspects of a culture, place and time, much like a map or pictograph.

My next step is to develop the skills I have learned in a way that honors their roots, using innovative adaptations of material and technique to relate them to my experience.

I'll keep you posted. Thanks for reading!